23: Neo-Feudalism and the Death of the Public Sphere

Published on 2025-04-08

Preparatory Readings:

Table of contents

- Review:

- 1. What is the Public Sphere?

- 2. Commercialization and Neo-Feudalism

- 3. Hope for a return to Public Sphere

- Example: Gary Web and the Dark Alliance Article

- Addendum: How Commercialization and Mass Culture Corrupts the Deliberation Process

Review:

Today we want to use our two articles to target three aspects of the “Public Sphere”.

-

First, we want a clearer picture of what the “Public Sphere” is, when it is working well, and the media conditions that enable the “Public Sphere” to work well.

-

Second, we want to identify why many critics believed the “Public Sphere” ceased to be operative in a real or authentic way in the 20th century and that changes in media and media markets were responsible for this.

-

Third, we want to get a hint of the growing excitement around the emerging Internet and why, for many, it held the promise of restoring the conditions necessary for a true Public Sphere to flourish.

Let’s consider each of these points in turn, using both articles by Habermas and Louw.

1. What is the Public Sphere?

Louw, quoting Habermas, provides a basic definition of the public sphere on pages 93 and 96. There are three main questions here.

How does Louw/Habermas define the Public Sphere?

What were the modes of communication that enabled/constituted the public sphere? How did people communicate? e.g. Who owned the medium? What kind of medium was it?

Why is dialectic critical to the Frankfurt School and Habermas’s idea of the public sphere? How do the above “media conditions” help ensure the “dialectical” nature of communication with the Public Sphere?

2. Commercialization and Neo-Feudalism

Next Louw and Habermas describe changing conditions in 20th century.

What is happening to media conditions in the 20th century?

For example, according to Louw, pp. 91-92, what is Garnham’s concerning with broadcasting regulations in the 1980’s?

Why, again according to Louw, p. 96, does the Frankfurt School think this critique extends long before the 1980’s and was already already operative from the 1920-1970s?

In short, Louw describes a process by which the deliberating bourgeoisie class, which previously aimed at “checking” administrative power, has now risen to the level of the ruling class. As such, their interest has shifted from preserving a space for deliberation to preserving the status quo.

This has involved a shift from preserving public spaces to the commercialization or privatization of space. Garhnam’s concern about the “auctioning” off of the broadcasting spectrum (in the name of “Consumer Sovereignty”!) is a good example.

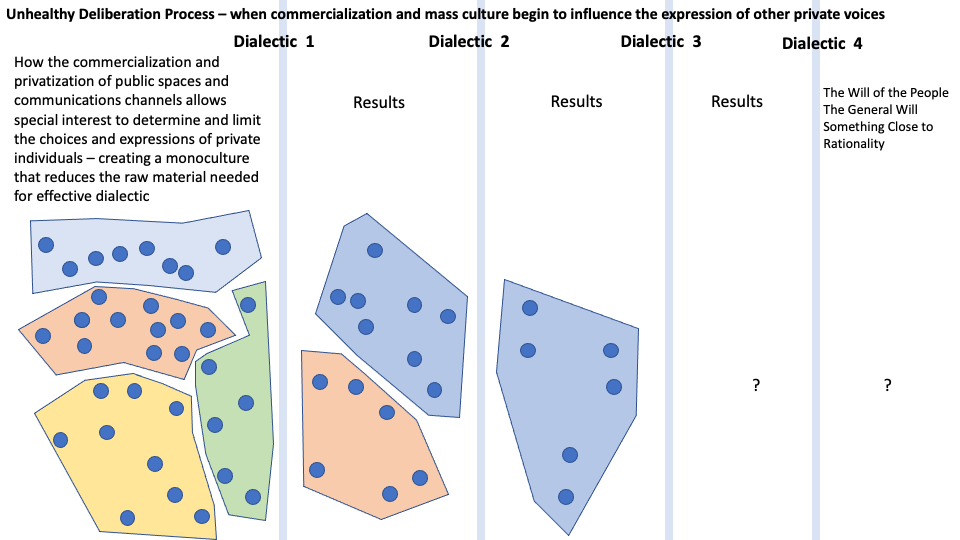

This commercialization or privatization has the effect of preventing “dialectic” through reducing a plurality of voices to one.

“Following Adorno and Horkheimer’s lead, the Frankfurt School argued that the culture industry was inherently undialectical and one-dimensional, producing ‘mass culture’ made by an elite group of professional communicators.”

Why does Habermas call this neo-feudalism?

It seems important that we call this “neo-feudalism” and not just “feudalism” because there is an important difference. The new feudalists are not the same as the old feudalists of the Middle Ages. The feudalists must now wield influence and control in a different way than the land owning aristocrats. Notably, their decisions must still appear to be justified by the “will of the people”.

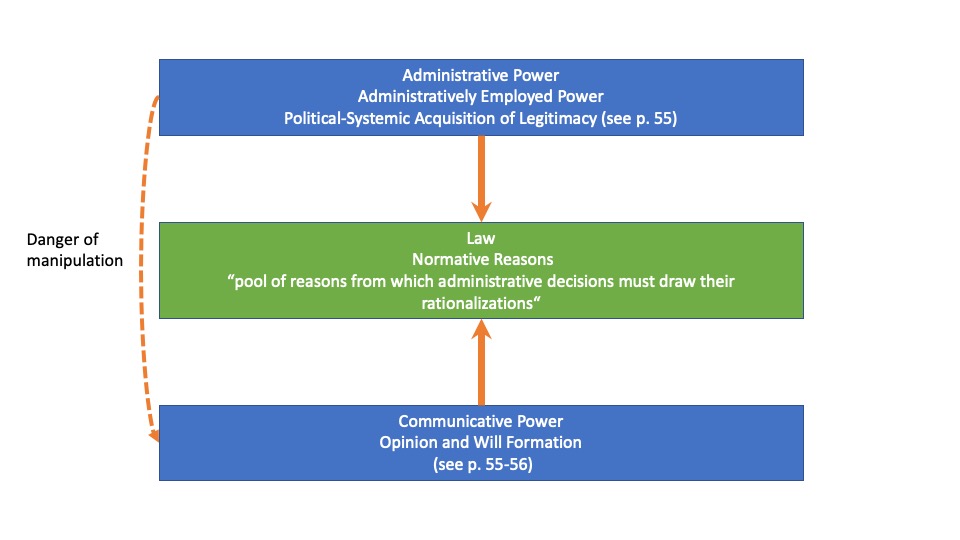

Thus in order to enact their private wishes, they must apply pressure to the communications apparatus that produces the “pool of reasons” from which they can rationalize their decisions.

In this regard, it remains important that there is still the appearance of a Public Sphere even if it is no longer there.

Habermas notes specifically that it was in the 20th century that we saw the rise of “professional communicators” (or public relations). The goal of these “publicists” was to “construct the idea” of “public opinion” (rather than “enable” public opinion to emerge) in support of the predetermined aims of private interest.

Habermas writes on the final page of our reading:

“At one time the process of making proceedings public (Publizitat) was intended to subject persons or affairs to public reason, and to make political decisions subject to appeal before the court of public opinion. But often enough today the process of making public simply serves the arcane policies of special interests; in the form of “publicity” it wins public prestige for people or affairs, thus making them worthy of acclamation in a climate of non-public opinion. The very words “public relations work” (Oeffentlichkeitsarbeit) betray the fact that a public sphere must first be arduously constructed case by case, a public sphere which earlier grew out of the social structure. Even the central relationship of the public, the parties and the parliament is affected by this change in function.”

See also my notes on the Habermas article, especially here and here

And Louw echoes this on p. 94:

“over time, the public sphere enmeshed with ‘representivity’ and managerialism, becoming merely a means to legitimate managerialists ruling elites. Habermas bemoaned the resulting ‘pseudo’ democracy which he said, effectively constituted a ‘depoliticized public realm’ (Habermass 1976:37) Hence, by the late twentieth century, although there was the appearance of political participation in Western democracies, the effects of offering voters ‘pseudo’ choices meant that politicians faced increasingly cynical electorates…”

Let’s spend sometime reflecting on this claim:

Can we think of some of examples in which subtle/hidden pressure is placed on public discussion, in order to produce a particular outcome, albeit cloaked in the legitimizing cloak of “public opinion”?

One might consider the tremendous role “public relations” firms have in determining what “news programs” and “newspapers” present to us as “news”. Consider one example here of Amazon pitching positive “news” stories to local news outlets

Louw, p. 94, refers to two-party systems as another example. How so? How does a two-party system determine the outcome of deliberation in certain ways, while suggesting that the outcome is simply the “will of the people? Why might this not actually represent what the “people” really want.

The Frankfurt School continually points to the way “private” control aims at producing a “homogenized” “mass culture” the weakens the ability for “dialectic” to function? What are some examples of the way “mass culture” tends to produce “pseudo public discussions” that are “undialectical and one-dimensional” (p. 96)? (See especially page 97).

3. Hope for a return to Public Sphere

Finally, Louw on p. 99, anticipates an objection to the trend describe by Habermas.

Louw writes:

“However, the last decades of the twentieth century saw the rapid growth of niche media.”

What does he have in mind here? How might the expansion of cable programming, for example, be a counteracting influence on the homogenizing forces of “mass culture”, thus restoring the chance for genuine dialectic to take place in the Public Sphere.

Why does Louw suggest this is NOT what is happening? (He provides 3 reasons on p. 99.)

- “Propensity for audiences to only pay attention to ‘their’ niche”. (p. 99)

- These niche spaces are increasingly independent from public control, and therefore architect-ed around ways to maximize profit rather than debate. “These privatized spaces are designed for commercial profit, not the facilitation of public debate”. (p. 99)

- “Most niches are still run according to the logic of top-down, manipulative communication, produced by professional communicators who target that niche to generate profit for their employers” (p. 99). i.e. each niche can still be influenced toward a particular goal. Consider for example, how Disney owns ABC, ESPN, HULU, Disney+ (and many other channels, studios, etc). In each of these niche places, it is possible for Disney to connect with its niche audience in a deeper way, and yet still steer each separate audience toward a goal that is advantageous for Disney.

Where doe Louw (and Enzensberger) see real possibility for “dialectic” to re-emerge?

p. 103: “Global information capitalists will be compelled to continually expand the world’s digital communication networks. The sheer size of the network makes it too large to control or to monitor or limit its uses fully. So just as the old bourgeois revolutionary ‘public sphere’ grew out of the Gutenberg print revolution, so too may new ‘human interactivities’ grow as a by-product of using the (as yet unimagined) possibilities inherent in the evolving digital networks”

Here the suggestion is that as global international conglomerates build the Internet as a way to facilitate their global reach, they are unintentionally building a communications network of criticism that is very hard to silence.

(This is a great transition to next class, where will look at Shapiro and the political excitement caused by the emerging digital media.)

But we might want to keep in mind that the Internet of the 1990s is much different from the Internet today.

First, why does it seem like the Internet of the 1990s might at first escape the three concerns (raised above) against the promise of niche media markets to restore the Public Sphere. (e.g. expansive cable programming etc.)

Second, to what extent is the Internet of today growing increasingly susceptible to these concerns?

Example: Gary Web and the Dark Alliance Article

Gary Webb was an investigative reporter for the San Jose Mercury who died from suicide in 2004. Gary reported an important article critical of the Government and the CIA. The reception and eventual tarnishing of that article is a good example of the kind of power that mass media outlets have and why many look to the Internet as a kind of escape from this kind of control.

The Gary Webb saga was recently made into a Hollywood movie, which I have asked the library to make available for you. So if your interested, the movie is available for you to watch here.

But let’s get a sense of the story from the trailer.

A key dynamic in this story, in connection to the concerns about “Neo-Feudalism” raised by Habermas, is that Gary Webb worked for a very small market regional newspaper, The San Jose Mercury. This very small paper did not have a national readership. It did not have a lot of money. Thus it did not have the financial backing to defend a highly controversial story against critique, whether justified or not.

Also relevant to our concern is where the loudest critiques of Webb’s story were coming from. Webb himself notes that the CIA remained largely silent to his reporting. Instead his story was heavily critiqued and dismissed by other newspapers. But these were not newspapers like his. They were “mass media” newspapers, backed by millions of dollars, controlled by elite power brokers.

The Huffington Post’s Ryan Grim provides a kind of summary article of the role mass media played in discrediting the story of Gary Webb in an article title Kill The Messenger: How The Media Destroyed Gary Webb

The article focuses on the Washington Post in particular and suggests that its close association with the power brokers of Washington incentivized the paper to take a critical and dismissive stance toward Webb’s article.

Grim captures this in the words of Douglas Farah, a former reporter for the Washington Post:

“If you’re talking about our intelligence community tolerating — if not promoting — drugs to pay for black ops, it’s rather an uncomfortable thing to do when you’re an establishment paper like the Post,” Farah told me. “If you were going to be directly rubbing up against the government, they wanted it more solid than it could probably ever be done.”

Why might the Post be hesitant to too overtly criticize the government? How might this effect their long term success as a newspaper?

Grim continues:

“Farah, now a consultant on the drug trade with the Department of Homeland Security, speculated that the Post’s proximity to the corridors of power made it beholden to whatever the official line was at the time.”

As Habermas noted this kind of influence is a big concern from the health of society truly governed by the will of the people. Recall:

In this image, we can see the danger. Habermas worries that the “administrative power”, while seemingly constrained by the pool of “normative reasons” it has to justify its action, can bypass this constraint if it is able to manipulate the deliberative/communications process that generates these “normative reasons”.

How might Habermas’s concerns be exacerbated now that the Post has be bought by Amazon CEO, Jeff Bezos? Could there be a more extreme example of private control over public debate?

Other journalists, like Beverly Bandler from Consortium news, have likewise seen the Gary Webb saga as powerful example of the ability of mass media to determine what does or does not get discussed in the public sphere.

“2) The concerted effort by U.S. major news media, specifically, the New York Times, Los Angeles Times and Washington Post to not only disparage the scandal but also discredit investigative reporter Gary Webb who, in 1996, revived the story by explaining the Contra cocaine’s impact on U.S. cities in the 1980s.”

Gary Web’s editor Dan Simon summarizes the saga as follows:

“The mainstream print media was ominously silent until October and November 1996,” Simon continued, “when The New York Times, The Washington Post, and the Los Angeles Times all finally picked up the story. But instead of launching their own investigations into whether the CIA had shielded drug traffickers, these papers went after Gary’s reporting, although they ‘could not find a single significant factual error,’ as Gary’s then-editor at The Mercury News, Jerry Ceppos, would write in an internal memo. “But after that, the series was described frequently as ‘discredited.’ Soon the story and Gary himself were spoiled goods. Gary’s editor switched sides and penned an apologia distancing the paper from the series. Gary was forced out of his job, even though the body of evidence supporting Gary’s account was actually growing. Two years later, the CIA’s internal investigation would prove to be a vindication of Gary’s work.”

Note a particular insidious problem here: even to the tell the story of the Gary Webb saga one has to rely on sources. Sources like “consortium mews” or even the Huffington Post – sources that see the story as an example of the power of mass media to silence independent news reporting – are themselves typically also niche publications – whereas major outlets like the Post and New York Times tend to be silent. (This makes sense sense: if the point here is that major news outlets need to be critiqued, one can hardly expect that these outlets will be eager to critique themselves.) But this creates a serious confidence problem for the general public. As the balance between niche publication and mass media publication grows, the problem of confidence and trust becomes more sinister and difficult to resolve. Niche publications are dismissed for being fringe; mass media publications grow more suspect because they seem invulnerable to critique.

In any case, it is fitting, in the end, if we hear from Gary Webb himself.

(This video is also important because it helps us transition to our theme for our next meeting. More precisely, Webb, at the end of the video, praises the Internet as vehicle to bring stories to light, stories that otherwise could not reach a national audience becomes of the costs of national publication and the control of the national market by a few powerful conglomerates.)

Video Discussion Anchor

Addendum: How Commercialization and Mass Culture Corrupts the Deliberation Process

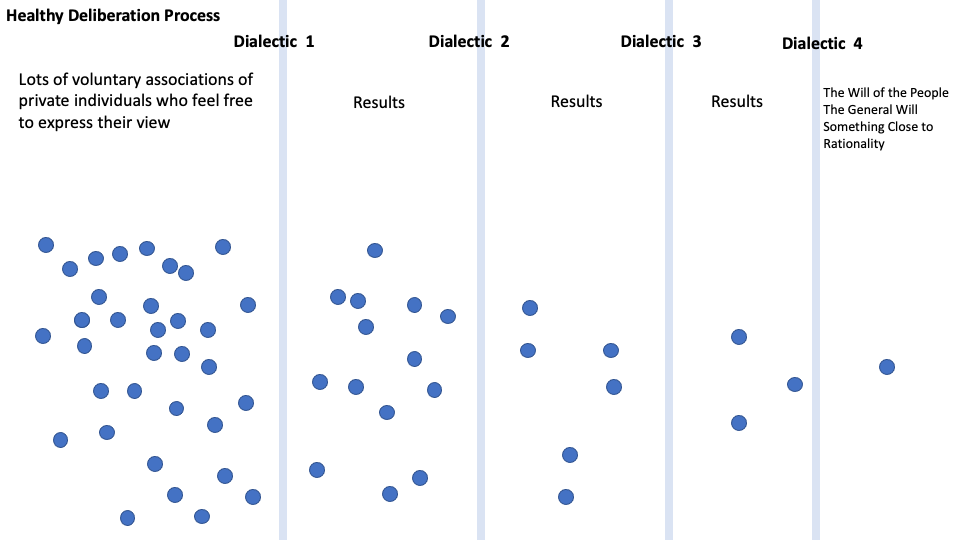

Here a few images that might help illustrate the way mass culture can subtly influence and weaken the deliberation process that Habermas looks for in the Public Sphere.

Here’s an example of what a healthy process might look like.

And here’s an example of what an unhealthy process might look like.

Habermas worries that either administrative power or powerful private commercial interest, through control of the channels of communication, can unduly influence the private opinions of others. This effectively reduces the amount of raw material needed for dialectic to work. With a growing monoculture, there is less diversity of opinion, and thus less potential dialectical conflict that can lead toward a synthesis that better represents the truth, rationality, and the “public will”.