22: Deliberative Democracy

Published on 2025-04-03

Preparatory Readings:

Table of contents

Review

With today’s reading, our goal is to continue looking at the foundational arguments used to support the equation that “more speech equals better deliberation”.

As we discussed last time, champions of deliberative democracy have long argued that freedom of expression is critical to the goals of a deliberative (rather than a direct) democracy. We began to see this in Kant’s What is Enlightenment. Today we to look closer at this argument in what is perhaps the most famous defense of freedom of expression, John Stuart Mill’s, On Liberty, Chapter 2, “on liberty of thought and discussion”. From there we want to look at an equally famous contemporary philosopher Jürgen Habermas (who relies heavily on the thought of Friedrich Fröbel) who points to some of the reasons why a “public sphere” is necessary for “deliberation” and some of the political challenges in creating that “public sphere”.

READING NOTE: The majority of our class time will focus on the reading from Mill, so please focus your attention there first. With the time remaining, we will try to pull out a few key details from the Habermas reading. I also recognize that the Habermas reading is quite difficult. So don’t feel frustrated if it feels difficult, because it is. Nevertheless it is an important primary source reading for us to be aware of and to wrestle with. So, I encourage you to “wrestle” with it for a while and also to use the course notes below to focus your attention on passages that I hope we can discuss in class. As noted below, I plan to focus primarily on section 4 (pp. 55-63).

As always, we want to think about how the desired effects of free speech (identified by Mill and Habermas) are dependent on more than just the written law, but also on the logic of the platform, architecture, or code that makes speech possible. Within these architectures, speech will happen in certain ways, at certain speeds, with certain costs.

Thus in the background, we need to constantly be asking whether or not the desired effects of free speech persists when the underlying assumptions about the platform of speech have changed.

Sunstein (as we will see in later chapters) does not always think these effects will remain when the platform has changed, and thus the equation, “more speech equals better deliberation” does not always remain true in our new media landscape. This is of course getting ahead of things. But it is important to keep it in mind, as this is where we are headed.

Mill, On liberty, c. 2

The argument of chapter 2 has a tight structure, but Mill’s 19th century writing and the lack of visual cues sometimes makes it difficult to follow.

However, Mill’s conclusion offers us some clues.

“We have now recognised the necessity to the mental well-being of mankind (on which all their other well-being depends) of freedom of opinion, and freedom of the expression of opinion, on four distinct grounds; which we will now briefly recapitulate.”

These four arguments revolve around Mill’s response to a central objection: if we know the truth, why should we, as a society, allow it to be contradicted by error.

I’d like to discuss each of these arguments in turn.

As Mill states at the outset, his response follows two main paths:

“It is necessary to consider separately these two hypotheses, each of which has a distinct branch of the argument corresponding to it. We can never be sure that the opinion we are endeavouring to stifle is a false opinion; and if we were sure, stifling it would be an evil still.”

First, he says we need to question the assumption that, since we as a society know the truth, therefore we do not need to hear these presumably false opinions.

Be prepared to provide an account of this argument.

What is the basic argument here?

What do you think about this argument? How far should this argument be stretched? Are there some truths so certain or useful, or are there some statements so false or dangerous, that it does not seem inappropriate to outlaw the expression of these falsehoods?

The argument then moves forward, by assuming the premise disputed in his first response. Let’s assume, he says, that society does actually have access to the truth. Are there still important reasons that a society might want to allow erroneous beliefs to be heard?

Noted as “second” in his final recapitulation but actually discussed last in his chapter (starting around p. 84), Mill notes that even if the received opinion (the dominant social belief) is “mostly true”, the opposing (mostly false opinion) still has some important part of the truth that it can deliver.

What is the basic argument here?

What examples does he give to support this argument?

What do you think about this argument? Is it strong? Why? Are there exceptions? Why?

But then he pushes the issue even further. Let’s assume (for the sake of argument) that a society’s beliefs were, per impossibile, known to be infallibly and completely true. In this case why should we not then censor opposing positions, which we know, again per impossibile, to be completely false.

Mill offers two arguments in this regard, arguments 3 and 4 respectively in his final recapitulation.

What is the third argument? (Hint: it has something to do with understanding the “reason” or “ground” of an opinion.) (See around p. 64.)

Again, we’re looking to test his argument. So…

Does the argument presume anything about the “platform” of speech? (such that the argument might not follow if the “platform” where changed?)

Are there any exceptions or extremes where his position about falsehoods improving our understanding of the truth would not follow?

What is the fourth argument? (Hint: it has something to do with understanding the “meaning” of an opinion.) (See around p. 72.)

Why is this important?

What examples does he give?

Again, we’re looking to test his argument. So…

Does the argument presume anything about the “platform” of speech? (Such that the argument might not follow if the “platform” where changed?)

Are there any exceptions or extremes where his position about falsehoods improving our understanding of the truth would not follow.

Habermas and the Public Sphere

The concept of the Public Sphere is an idea that today is closely associated with the name Jürgen Habermas.

In this, admittedly very difficult article, I hope we get a sense of 1) what he means by Public Sphere, 2) why this is needed in addition to the official deliberating bodies (such as the “Senate” as conceived by the Founding Fathers, 3) and a sense of what he thinks it takes to maintain this kind of Public Sphere.

My focus here is primarily on section 4 (pp. 55-63). But let’s just note a few preliminary things.

Habermas walks us through a political history already somewhat familiar to us. Rousseau is key player in this story, as Rousseau did not want to accept the dichotomy between “liberty” over “equality”. Instead he wanted to find an arrangement in which everyone’s liberty and peace were protected but at the same time everyone remained autonomous and thereby equal.

But Rousseau’s theoretical ideas were difficult to realize, and critics rightly worried that the “will of the people” would inevitably become the “tyranny of the majority” or even the tyranny of the most politically active or the loudest shouters.

In section 2.2, p. 46, Habermas points to both Mill and Fröbel as examples of thinkers who argued that, since the majority obviously cannot represent the General Will (the “will of the people”), it must emerge through the established procedures of deliberation; voting and subsequent discussion by official deliberative bodies.

Here, Habermas is really calling our attention to Fröbel and Mill’s preference for a deliberative democracy over direct democracy, which echoes the intention of the founders of the American constitution when they created the Senate as a kind of cooling force against the passionate, prejudiced, and irrational voice of the “mob”.

What follows in section two and three is an elaborate defense of the need for “deliberation” and “open discussion”, along the lines of what we have seen in Mill.

In section 4, Habermas tries to take us one step further.

First he recaps how deliberative bodies function as a check on administrative power.

He writes:

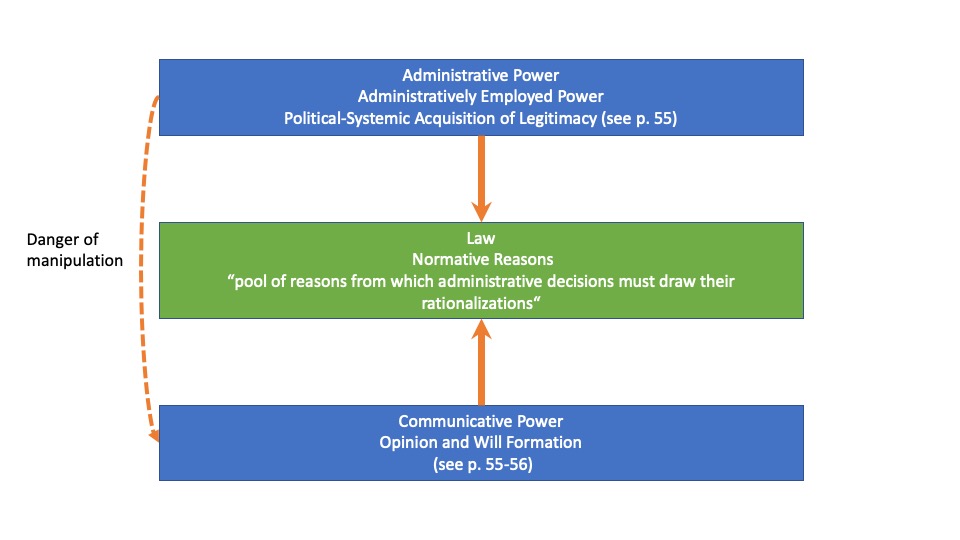

“Normative reasons, which justify adopted policies and enacted norms in the language of law, are regarded in the language of administrative power as rationalizations appended to decisions that were previously induced.”

In other words, executive/administrative power, in being responsible for action, is required to rationalize its actions. Deliberative bodies constrain administrative action by constraining the pool of normative reasons that can be appealed to in order to justify action.

Again he writes:

“Communicatively generated legitimate power can have an effect on the political system insofar as it assumes responsibility for the pool of reasons from which administrative decisions must draw their rationalizations. If the normative arguments appended by the system have been discursively invalidated by counter-arguments from prior political communication, then it is simply not the case that “anything goes,” that is, anything feasible for the political system.”

I illustrate this below as follows:

But Habermas notes next, there is a danger here of manipulation. The executive/administrative branch can extend its power by manipulating the process of deliberation and subsequently affecting the “normative reasons” it has at its disposal to justify its actions. (Consider how propaganda is used by a government to manufacture justifications for its actions.)

The “elitist” answer (as Habermas calls it on p. 57) to this problem is to develop institutionalized deliberating bodies (like the Senate or Parliament) to prevent the manipulation of the masses by those that wield executive power.

But what problem does Habermas believe he has found at this point (p. 57)? Why has Fröbel overlooked something?

“if the voters’ opinion is irrational, then the election of representatives is no less so.”

To resolve this dilemma, Habermas thinks we need to pay attention to something new: namely the relationship between “political will-formation” and the “surrounding environment of unstructured processes of opinion-formation”.

Here he argues that in addition to organized deliberative bodies that are responsible for reaching decisions, unofficial, spontaneous, “unsubverted circuits of communication in the public sphere” are needed.

He describes these as:

“Voluntary associations represent the nodal points in a communication network that emerges from the intermeshing of autonomous public spheres.”

This might look something like the following:

Evidence of the power of the power of the voluntary associations, he suggests, can be seen in the correlation between voting behavior and the general mood of political culture. (Voting usually follows the political mood of a country as expressed through various informal spontaneous modes of political communication.)

This un-official political culture is required in order for official deliberating bodies to do their work.

“Naturally, even a proceduralized “popular sovereignty” of this sort cannot operate without the support of an accommodating political culture, without the basic attitudes, mediated by tradition and socialization, of a population accustomed to political freedom: rational political will-formation cannot occur unless a rationalized life-world meets it halfway.”

In sum: According to Habermas, then, critical to the health of a democracy is the health of the “public sphere”. This network of voluntary associations is what ensures the independence of the official deliberating bodies, which in turn ensures that executive power is controlled by the sovereignty of the “rational will” of the people.

Final note: While difficult to grasp, it seems important to note the idea that the public sphere “reproduces itself self-referentially” (p. 58). (Consider the paragraph at the bottom of p. 58 and extending to page 59.) Here I understand him to mean that the debating public, in their freedom to communicate opinions and beliefs is – at the same that they are debating and arguing – generating something shared; a shared consciousness of their participation in the public sphere and its generative power of the “General Will”.

This seems important in relation to the thesis of Sunstein. Here the act of communication – even if what is communicated is in conflict – generates something common and collective (the kind of “shared experience” noted as critical by Sunstein). This also reminds one of McLuhan’s thesis that the “medium” is much more important than the “message”. The “message” may be one of disagreement, but its communication through a medium generates a sense of something “common”. We should be attentive then to the communication platforms/architectures that allow this collective self-consciousness to emerge, and perhaps worry with Sunstein about the emergence of forms of communication where this salutary side-effect is not produced.

With this in mind, let’s engage in a little bit of final reflection together.

First, can we identify some examples of the kind of unorganized “voluntary associations” Habermas has in mind?

How do we know when these associations are healthy and performing the function Habermas has in mind?

What might these associations look like in a pre-digital world? How would they communicate? Do the communications platforms enable or disable the kind of social function Habermas expects from these groups?

Would AOL chatrooms, MMOGs, USENET, or facebook groups today count as such associations? Why or why not? How might they be similar or different from such groups in a pre-digital world?