Indices and Classification

Indices are an important technical advance and technology for dealing with information overload. We don’t always think of them as specific technology or invention. They are so deeply intertwined with our books, such an essential part of our expectation of what a book should be, that it is easy to forget that it is something that had to be invented, then designed, and finally implemented as a specific kind of data-visualization.

Because the index is an invented tool rather than some simple extension of nature, it is also hard to see the limitations of its traditional form and in turn it is easy to overlook how it might be improved.

In this post, I want to report out on the progress I’ve made with a new kind of index that I want to make available for scholars of the medieval scholastic corpus.

Index as Finding Aid

Certainly, one function of a traditional index is a finding aid. In this case, a user knows what they are looking for and simply wants to be directed to the passage of interest.

Within the confines of the the physical container at hand (i.e. the current book in hand) this might seem to work well enough. But the look up friction is not to be underestimated: the flipping of pages, losing one’s place, or the act of recording pages numbers in a separate list in order to avoid the flipping of pages are all examples of friction that slow the process and can ultimately disincentivize an exhaustive survey.

Moreover, the unwieldy flipping of pages in exacerbated in any attempt to compare indexed passages. Let’s say you were looking for all the references to Augustine in a given text and you wanted to compare how Augustine was cited or referenced. Once you’ve found the pages numbers in question, the ability to lay out these found passages side by side for comparison is quite difficult and requires quite a bit of page marking and page flipping. We can do better.

Beyond these limitations, its the boundaries of the container that really expose the limits of this method. With respect to an index of sources, the source being referenced often remains out of reach. Extending the previous example, imagine our goal is not just to compare the way Augustine is referenced, but to compare the actual text used in the author’s citation with the original passage of Augustine. Has the author taken liberties with the text of Augustine? Are they prone to paraphrasing the text or do they quote it verbatim? And if there are multiple surviving versions of a text with their own variations, which versions or witnesses is the author citing? An index bound to its containing physical container cannot help us with these questions. The most it can do is point us to another container in another place and hope that we have the time and energy to manually locate the source and continue with the comparison.

The presence of machine actionable links changes things. The machine actionable link, first, means that instead of sending a user to different places on interest, we can bring the points of interest to the reader. No more flipping pages. More importantly, it explodes the boundaries of inside and outside the “physical container”. No longer are we limited only to the active quoting passages. We can invert these links and point with equal granularity and precision to the passage being quoted or referenced.

Index as Classification Tool

But beyond using an index as tool to merely find what we are already looking for, there’s another more subtle way we use indices. If you’ve ever begun a research project by going to the library and selecting 20 or 30 books that might be useful to your work and then began scanning the indices, table of contents, and bibliography to get a sense of the kind of material discussed in said book, then you have used an index as a classification tool. Running through an index, we try to get a sense – based on who quoted and referenced – of what the book is about and who its main conversations partners are. Based on this survey, we might sort the books we have selected into different categories and then prioritize different sets of books based on what kinds of conversations seem most useful to the present research task.

This kind of classification is, however, made difficult by the static nature of the medium and the way each index is confined to the boundaries of its own container. In order to sort and compare the books in questions, our hypothetical research had to manually traverse the library, carry the 30 books to a desk and then start combing the indices one by one. Even with 30 books this seems like a labor intensive task. Imagine doing this for 100, 200, or even 1000 books.

It is also possible to imagine how this kind of classification could be used to sort parts of a given book. Based on whose is cited, Chapter 1 seems to be about X, while given the references in chapter 10, it seems to be more about Y. This seems possible, but the medium makes it extremely difficult. The printed index’s mechanism of linking through page numbers (the material hierarchy) is arbitrarily related to the meaningful units of text (the content hierarchy). Performing this kind of classification would require the user to retain a mental mapping from page to text unit that they constantly refer to as they scan: e.g. “chapter 1 appears on pages 1-10, chapter 10 appears on pages 143-162”. This seems infeasible.

Finally, imagine if we wanted to combine the above two methods. Imagine if we wanted to classify distinct granular sections within an individual book to conceptually parallel granular sections in other books. Encyclopedic-type works come to mind. Imagine I wanted to compare an entry on God in 100 different encyclopedias spanning 100 years. Here it might be quite interesting to see how the conversation partners and authorities quoted in these entries change or evolve over time. We might also want to group these entries by the kinds of authorities they use. Such classification could reveal the core beliefs and/or biases of different entries. Based on their citations, these entries are likely by Roman Catholic authors whereas these probably come from the Reformed tradition. Or we might even want to see how the authorities used within the Catholic or Reformed tradition have changed over time.

The traditional index makes all of these desired outcomes difficult if not impossible. But machine actionable links combined with detailed domain specific data in a well-designed knowledge graph can change this.

A New Kind of Index

Here I introduce the index tool I’m working which can achieve the desired outcomes listed above: namely immediate lookups/comparisons and dynamic classification.

Let’s take a look at the first example below.

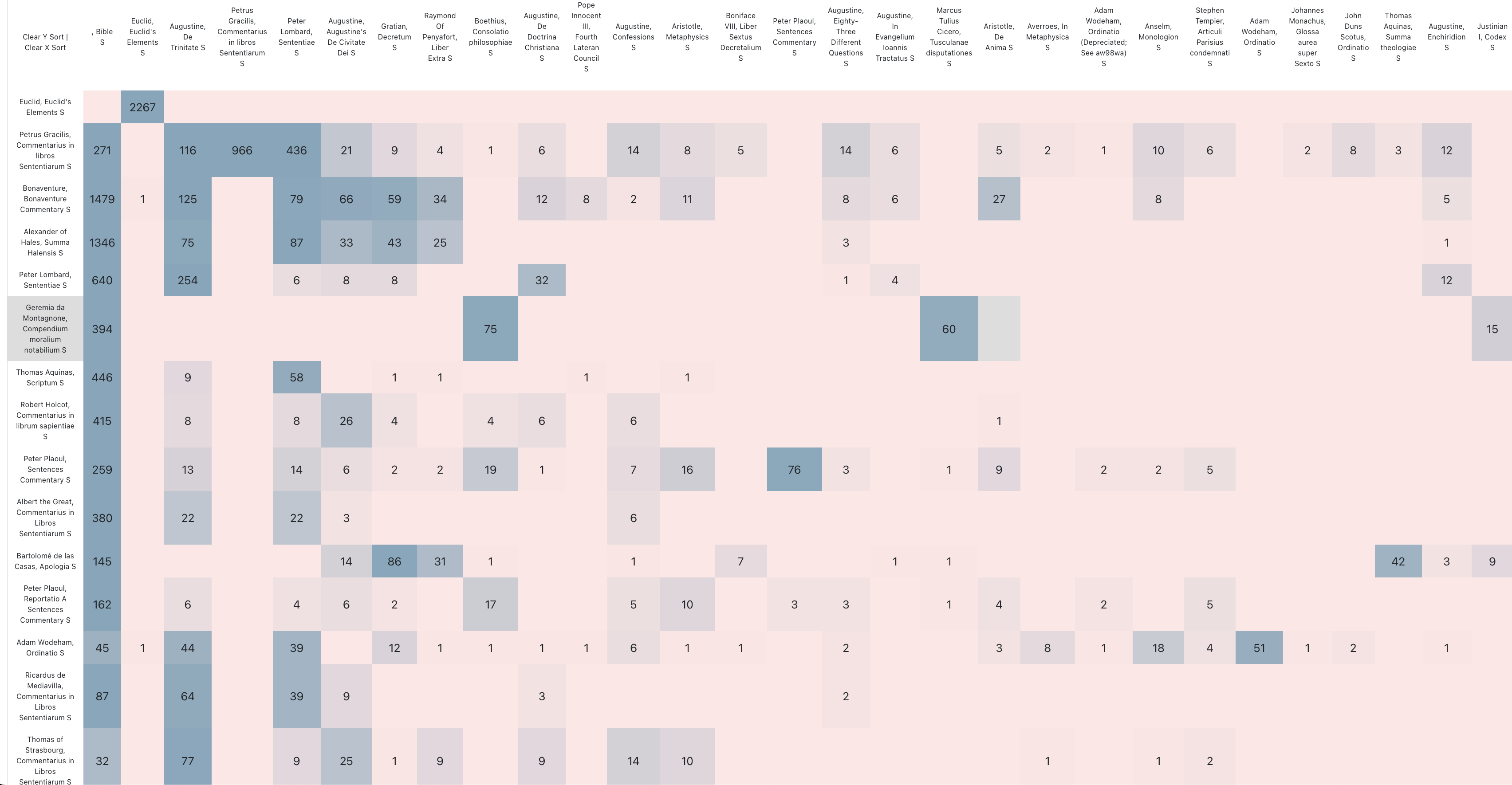

In this interactive lombardpress web-component (which you can explore in the lombardpress components library) a user can consult any text at any level and ask for its citation frequency of any other text (and here’s the important part) at any level of granularity.

In the above image, each top level text is shown with its citation frequency of every other top level text.

This is an index of more than 16,000 entries. That’s a lot to take in. Certainly, this offer us enough information to do some broad classification. All the texts that cite Augustine’s De Trinitate probably have some kind of theological focus. All the texts that don’t, probably have a different focus. But with so many texts, even scrolling through and accurately discerning these variations seems like demanding and tedious work. It’s also unnecessary. If we treat this index of indices as a matrix, we can classify the different text rows using methods like Principal Components Analysis and plot these texts in a two dimensional space. Any early provisional result based on existing data can be seen below.

Classification here however remains difficult because of the kinds of medieval texts that are indexed here. Medieval commentaries and summa function much more like encyclopedias than as independent treatises. As such, at the top level, there subject matter is extremely diverse, spanning a very wide array of topics. This is a case where it would be beneficial to break these larger texts into meaningful conceptual pieces and then resume the comparison.

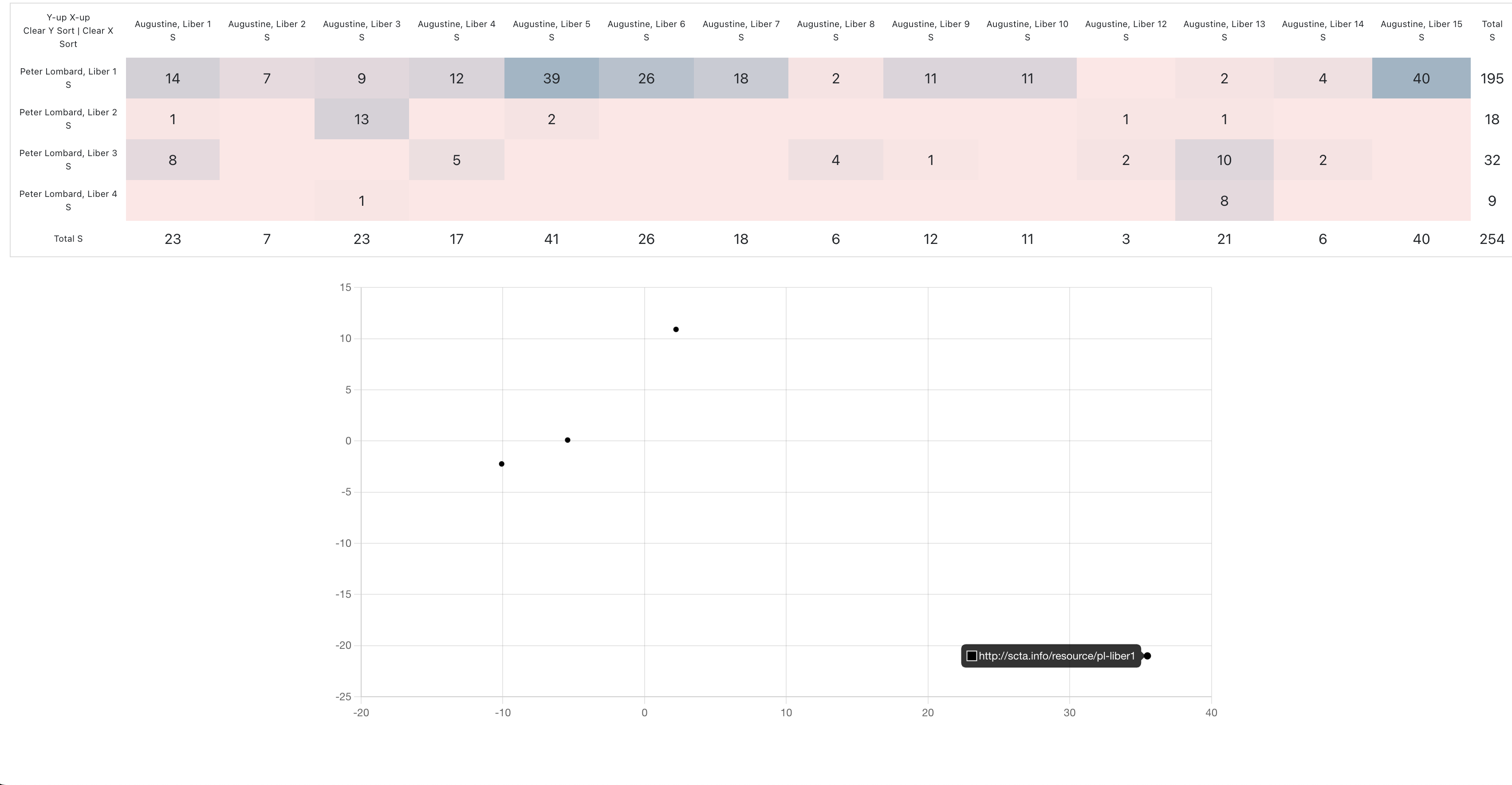

Consider the example below. Here we compare the four separate books (the 2nd level of the hierarchy) contained with Peter Lombard’s Sentences with the individual books of Augustine’s De Trinitate (again, the 2nd level of the hierarchy.)

Here the PCA technique is already giving us a much more meaningful classification. The initiated know that, generally, Book 1 is about God, Book 2 is about Creation, Book 3 is about Christ, and Book 4 is about Christ and the Sacraments. And we can see in the PCA plot a separation that reflects that fundamental division.

Having refined our classification, one can go deeper. If we click on any of the values in the X or Y axes or any of the cells with a frequency count, the index takes you a level deeper into each text. The PCA analysis will once again cluster the component parts at the current breakdown level.

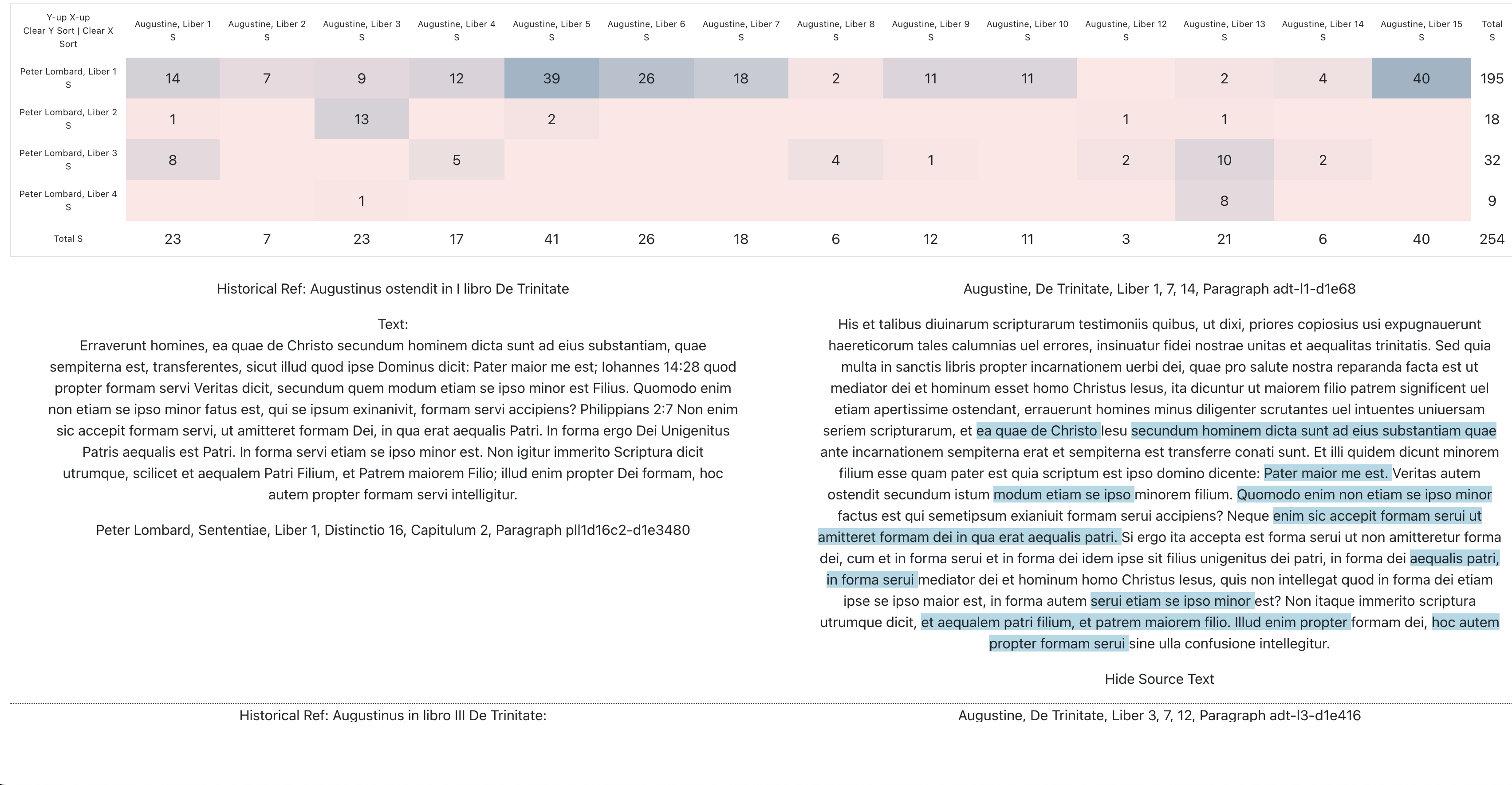

The index also excels at the lookup task that we first associate with any index. But here, of course, instead of sending you away to view the text, it enables the users to see and compare the quoting and quoted passages immediately within the context of the current view.

If we select “show citations”, then, as seen below, we can explore the actual text of each citations and view these quotations compared against the source text.

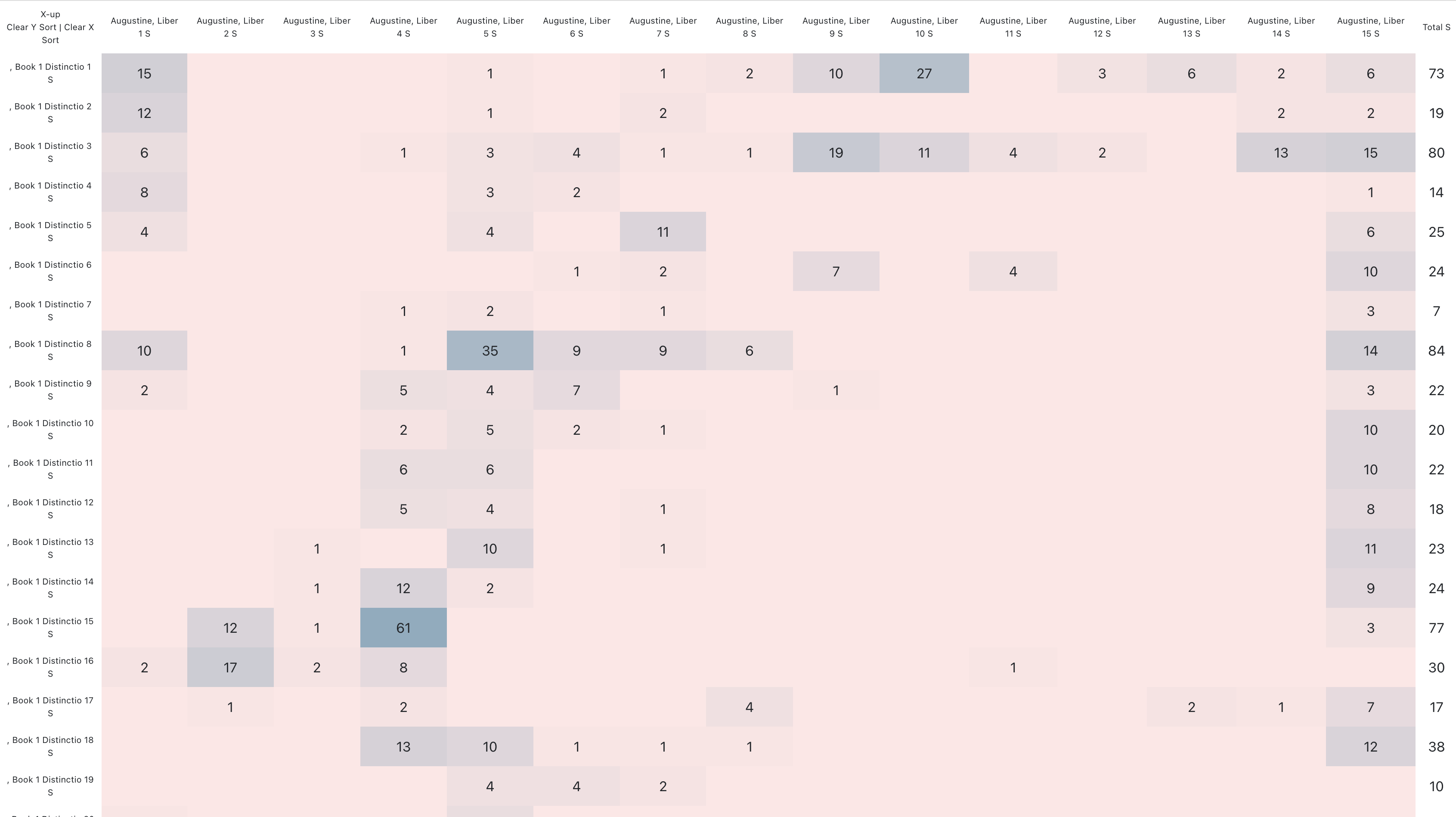

Finally, let me just point to one advanced form of grouping that I’m excited about. In the case of a commentary tradition like the tradition of commenting on the Sentences of Peter Lombard, since each distinction is is own topic, I might want treat the entire sum of what was written on distinction 1 as a distinct text and compare it other distinctions.

Here again the encyclopedia example is helpful. It might be interesting to know what are the common authorities used in all encyclopedia entires on God regardless of who the author is. Here I might want to see which authorities or parts of authoritative texts are common and which are unusual. I might want to compare this to other articles. Do any of these same texts or authorities get used in surprising places? And once I have a trend for the tradition, I might want to start looking at exceptions. Which articles innovate or deviate from the tradition by citing an uncommon authority? If we arrange this chronologically, we could also see cases where, when a given article introduces a previously uncommon citation, it suddenly becomes common in the subsequent tradition. This would be a real discovery of influence.

Such perspectives are possible for the Sentences commentary tradition and commentary traditions like it.

In the screen shots below I offer two brief examples.

Here I show the frequency of citations from Augustine’s De Trinitate in each of Sentences Commentary distinction. Note again this does not represent the citations found merely in Lombard’s distinctions, but in all of the commentaries on the distinction in question.

This perspective offers some interesting detail. For example, we can notice that its very common in distinction 1 (usually treating the topic of happiness or beatitude) to quote from Books 1, 9 and 10 of Augustine’s De Trinitate. While it is much very uncommon to see reliance on passages from Book 5 or 7. The rare and deviating use of these passages is worthy of closer inspection.

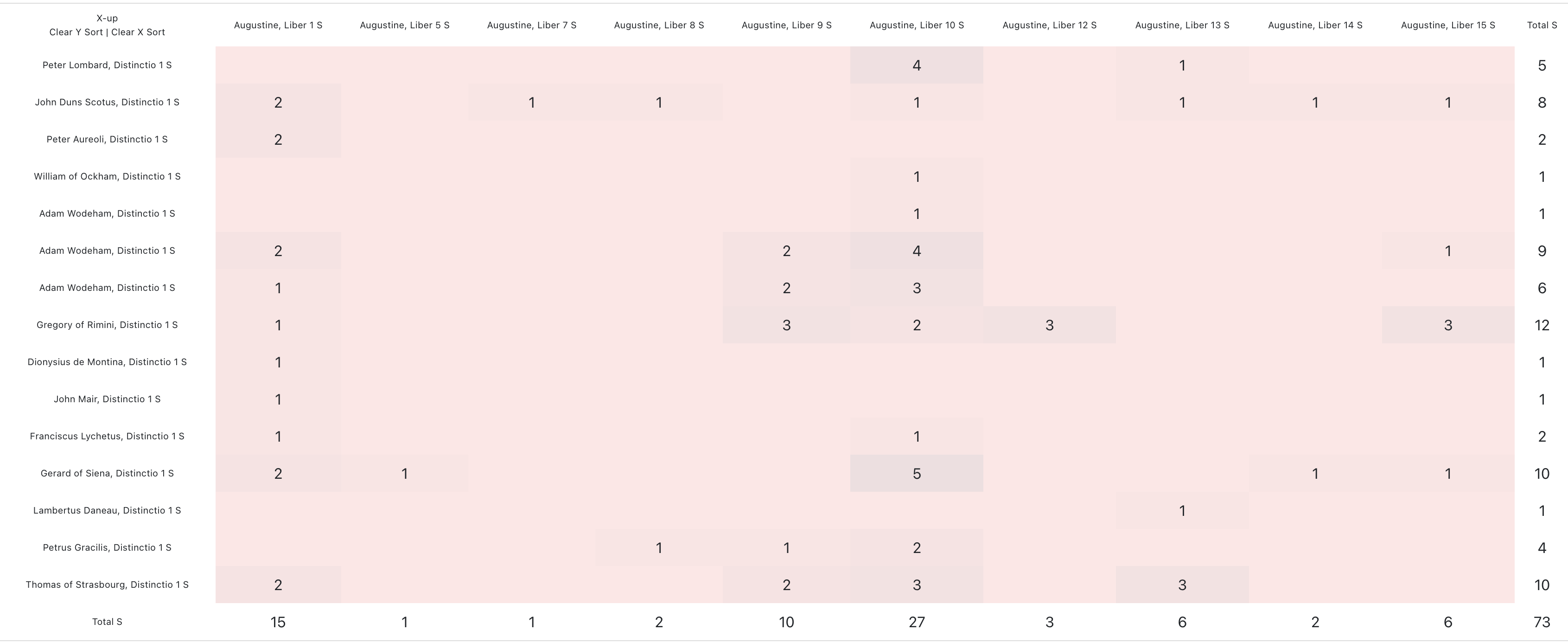

In the next screen shot, we can isolate our interest to just distinction 1. But instead of aggregating them all together, we can now disaggregate them by author to see where the deviation occurs.

As we can see here, the Augustianian Gerard of Siena is unique in his use of a passage from Book 5 and and Scotus is unique in his use of a passage from Book 7. These are exceptions we could explore to learn about what they found interesting these passages that other ignored and how the passages influenced their overall position relative to others.

That’s it for now. Thanks for reading. Comments and questions are always welcome.

Here again is my live demo on youtube (feel free to leave comments in the comments section):